CONTRIBUTION

The Exhibition is in Transit vol. 1 : Jade Foster

Jade Foster, something to nothing to an utterance: a sermon of black performativity (2021). Text and digital image. Courtesy of the artist.

This text is an unfinished, notational offering: a gift of generosity within a period of scarcity, where black [read: not politically black] bodies are the subject of heightened political attention. In turn, there is currently an unsettling hyper-visibility, performative activism and allyship towards the support of black cultural production and cultural workers within the arts sector. This text purposefully contains unfinished, disjointed and sporadic notations and thoughts that have been oscillating in my head for years. Unfinished because I am struggling to function within crisis, constantly moving from house to house, struck with illness or feeling overwhelmed from how cultural organisations leech my labour, offering precarious and low paid salaries in return. I have kept all of this in mind when writing.

My intended audience flows between academia, cultural gatekeepers, supposedly well-intended allies in the visual art sector, and black artists or curators (my community). I hope this text speaks to these people at various moments; and anyone interested in my musings.

-

In the UK, 'stay at home' has been the message throughout lockdown and the new norm for engaging with publics. Should we consider what is defined by art institutions as 'public programming', a more effective mode for exhibiting?

I believe the artistic use of discourse is a form of art-making transmitted through the exhibition form. This essay will briefly interrogate the notion of liveness and transmission in the context of black performativity, speech, and language in time-based media and live art. The text offers an introduction to 'curatorial frequency', a theoretical and conceptual framework for a way of being live whilst attentive with these mediums during and after a crisis.

Thinking heavily about the futility of curatorial and artistic practice (1) within global emergencies, I am continuously conflicted in my role as a curator within a crisis. I feel the need to reconstitute what it means to publicise artworks created within periods of precarity and social and political instability. Curatorial practice's efficacy in a volatile circumstance lies within drawing attention to how crisis implicates our lives. How useful is social and political contemporary art in commenting on emergencies (think pre-covid to the HIV and Aids epidemic, black deaths caused by police) when it exists within an exclusionary art world? Is it enough to only comment? Or do these practices need to actualise change? Can artworks be operative rather than simply illustrative?

Stuart Hall articulates simply within his essay Encoding and Decoding in Television Discourse: "Before this message can have 'effect' (however defined), satisfy a 'need' or be put to a 'use', it must first be appropriated as a meaningful discourse and be meaningfully decoded". He continues, "It is the set of decoded meanings which 'have an effect', influence, entertain, instruct or persuade." (2)

Aria Dean, Eulogy for a Black Mass (2017). Digital video, 5:54 mins.

You could compare this communication model, which is about television discourse, with durational artworks that use appropriated media and speech. Through art-making, digital content such as memes, news broadcasts or reports are decoded into meaningful discourse through oration and storytelling (whatever artistic form that takes). When working with sound and moving images, the artist could be considered as a decoder, undergoing close semiosis and establishing meaning with a complicated set of signs for audiences. A curator then further decodes the artwork or material and considers how the message can be presented and disseminated.

Within Aria Dean's Eulogy for a Black Mass (2017), she speaks "memes have something Black about them. This something is complicated and hard to make recognisable. It has to do with a lot of Black people making memes, caressing them, carrying them to and fro, spreading them'…' all the creative labour of the Black collective being aside, there is a palpable Blackness to much of this viral content, especially memes that circulates independently from actual Black people. There is something Black about this content that goes beyond its scope. This something seems to require an infinite loop of referral to describe and is itself infinitely self-referential." To thrive within new visual language forms and envision Blackness as plentiful, not defined or tethered to a corporal experience is transformative. Black performativity within the digital realm is an unfathomed and complicated system of signs with emancipatory and liberatory qualities. Why would we want to fathom Blackness as something that can be contained, manipulated, and controlled? Black visual life is constantly exhibited, in transit and within constant transmission on the internet at a rate that cannot be held within or clearly defined. From TikToks to Memes, Black bodies aren't experienced within the binary of pain or joy but within an emotional spectrum that isn't bound to the singular.

Martine Syms, Notes On Gesture, video still (2015). Digital HD video, 10:30 mins, United States, English, 16:9.

The narrated stories artists produce within a digital sphere, through broadcast, have the potential to evolve into an act of refusal or hope (speech acts). As Toni Morrison states, "We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal." Black cultural practitioners are thriving in new visual languages, doing language, reclaiming and disrupting—as they have always been. We practice affirmation, negation, refutation and refusal. For the Practicing Refusal Collective co-founded by Tina Campt and Saidiya Hartman, "practicing refusal" names the urgency of rethinking the time, space, and fundamental vocabulary of what constitutes politics, activism, and theory, as well as what it means to refuse the terms given to us to name these struggles." (3) This is not inactive or idle work to undergo in a moment of crisis.

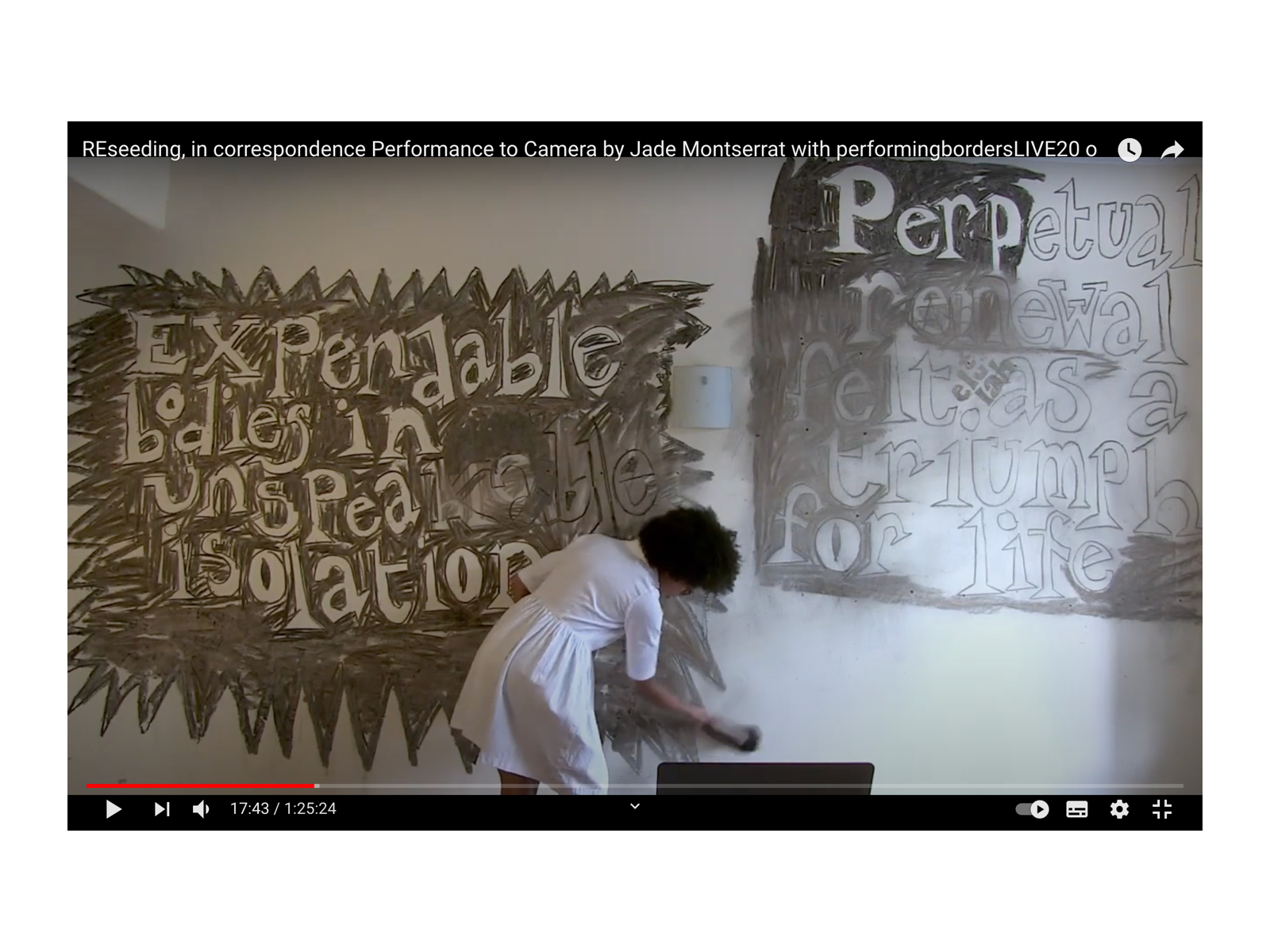

Notable works that speak to this are Notes on Gesture (2015) by Martine Syms and RE:seeding, in correspondence Performance to Camera (2020) by Jade Montserrat and Webb-Ellis. Syms’ work focuses on the language of the hand, which is “inspired by a riff on a popular joke, ‘Everybody wanna be a black woman but nobody wanna be a black women’ ” The video work uses the 17th Century text Chirologia: Or the Natural Language of the Hand as a guide to the creation of an inventory of gestures for performance. RE:seeding, in correspondence Performance to Camera, explores the “notions and lived experiences of body, land, and ownership while exploring modes of online and offline communications with migrant communities in times of health, social and political crises.” (4)

RE:seeding, in correspondence Performance to Camera (2020) by Jade Montserrat and Webb-Ellis. Commissioned by performingborders for performingbordersLIVE20.

When writing about black performativity, it is important to analyse hostile conditions where culture is produced and black cultural practitioners work. Marginalised and racialised communities, Black people, are relentlessly entangled within a consistent state of calamity and adversity when our lives are valued as less than human. These communities are trying to stay (a)live, especially if “each new deprivation raises doubts about when freedom is going to come” and the question repeating in the head of these communities is 'Can I live?' (5). Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley's artwork WE ARE HERE BECAUSE OF THOSE THAT ARE NOT is an archive of Black Trans Experience amalgamating animation, game design, and sound. Brathwaite-Shirley created the work to preserve life, where wayward lives (6) are not forgotten and erased. The work is both an offering of tenderness and strength that was designed by and for Black Trans people. The low-frequency sound is deepening, and the narration is affirming, encompassing black performativity that resonates as urgent and affecting. Braithwaite-Shirley's work exists alongside other works by artists who speak directly to their community. Art isn't synonymous with pleasure, and it isn't always comfortable to engage with; I would argue that the most affecting artworks can never be.

Barby Asante, Declaration of Independence (2019), BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art installation view Photo: Colin Davison © 2019 BALTIC

Social and political art cannot be radical unless it vigorously addresses survival within a crisis. It should embody a process of "Decolonization, which sets out to change the order of the world...a programme of complete disorder. But it cannot come as a result of magical practices, nor of a natural shock, nor of a friendly understanding.”(7) I would strongly argue that individual artists can't have an affecting decolonial practice; contrastingly, art movements hold the most potential in the art world for radical practice and restitution. Art movements existing adjacent to resistance movements can incite change. Artistic practices that are fugitive, forcefully destructive to the status quo, expose and dismantle the law's oppressive constraints need to be centred within these movements. Radical cultural practices contemplate healing and survival after resistance and imagine what can build from remains, in the wake of (8) and despite persistent systemic violence.

My proposition is a clear break away from the main UK art world that centres around Arts Councils. Instead, establishing a communication system centred on closeness both discursively and economically among marginalised people at the edges of the existent art world with new decentralised funding bodies led by and for marginalised workers. To achieve this requires a complete revolt and a declaration for more equitable conventions and laws within the art world (a separate art world from the one we operate within) that governs us.

This isn't a search for newness but a refusal to accept the current state of play. It needs a seismic shift of culture that instigates a widespread cultural phenomenon in which marginalised people are no longer completely reliant on an exploitative system to get by. There needs to be a cultural and economic change in rates of pay, where the sectors labour and cultural workers aren't aspiring to ‘just get by’. I envision a Magna Carta/social contract/A written Declaration of Independence/THE Document/THE Partnership Agreement/THE Access Rider/THE Handbook that contains many smaller handbooks or whatever you want to call it. This should be systemically implemented among those at the peripheries to protect the lives in which the art world continues to fail the most. If a funder, institution, individual, organisation etc. fails to recognise and adhere to it, we should not engage.

The system needs those at the periphery for survival: cheap labour, reaching their quota, getting more funding, and obtaining more power, but we should not give our labour willingly. Such a phenomenon or movement would need unilateral support and unity within our communities across sectors. It cannot be an art movement; it has to be a resistance movement, a revolution, standing in solidarity with the feminist, civil rights movements and any movement trying to eradicate Racial Capitalism; to do the actual work of social change and decolonisation. UKartists4BLM, Black Curators Collective, Migrants in Culture, and others also seek transformation through refusal.

In the UK, I see many people speaking out regarding government restrictions during the Coronavirus pandemic, demonstrating how oblivious some of the UK population are to existing health inequalities – if it doesn't directly impact them. Being in a state of restriction through a crisis is not a new concept or life experience for people on the periphery, born into a life where they face the deepest entrenched social inequalities. Restriction and scarcity are familiar contagions. We exist in unprecedented times but navigating an inaccessible healthcare system is not an unparalleled experience for racialised communities, especially those that have and continue to seek refuge in the UK. The list is endless, from the lack of rights for transgender and non-binary people to access lifesaving healthcare to Institutional Racism playing out in patients' everyday encounters.

Art feels very futile in the current state of crisis.

What can curators do when we feel inattentive towards the sector?

Jade Foster, Intention, video still (2020). Curating Borders, Curators Platform Commission for performingbordersLIVE20. Courtesy of the artist.

The idea of my work being efficacious or worthwhile runs in my head every time I log onto Office 365 or go into a Zoom meeting with colleagues. With the saturation of digital technologies coupled with the constraint of movement within my every day, I find it incredibly difficult to stay present. My engagement with people and art is currently solely mediated and experienced only through computing devices.

Attempting to stay present, attentive, and engaged catalysed my thoughts about liveness (in the context of live art). Liveness is a physical experience of witnessing a performance that happens in real-time; but could equally be seen as the effort to sense and respond to change or transition whilst unfolding. Liveness is the ability to be in transit and sustain collective resonance between artist and audience, curator and audience, and artist and curator in-between or during live occurrences. This type of activity does not need to be an entirely public-facing experience within an ‘event’ or ‘exhibition’ form; it can happen intimately, privately and closed-door. Whether an online exhibition consists of born-digital work or documentation of physical work, it can be experienced at home, alone. Experiencing digital work doesn't necessarily require travelling to a physical building, and therefore behaviours around how exhibitions are encountered continue to shift.

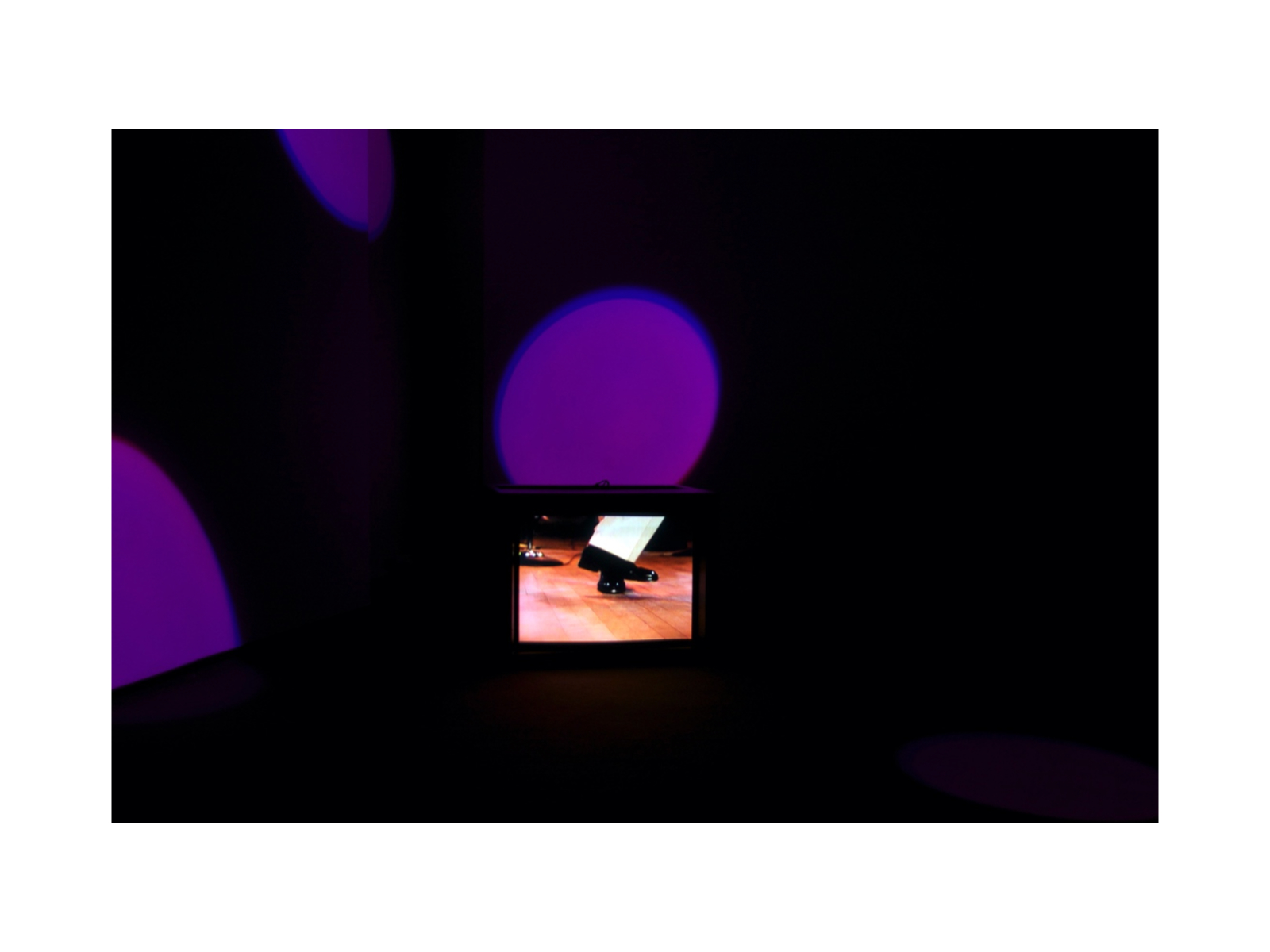

Appau Jnr Boakye-Yiadom, 4minutes 6 of Conversation 2014-. Installation: 4:06 mins video (appropriated archive footage) viewed on a Sony 27" cube monitor, a set of 6 sound sensitive LED disco lights, amplifier and speakers. Installation shot.

Appau Jnr Boakye-Yiadom, 4minutes 6 of Conversation 2014-, video still of Live Performance V22 Part 1, Drumming by GEO (T&I: @_GeoMusic).

In saying this, I understand liveness as a very temporal experience consisting of the spacious present (9); real-time audio frequencies, kinetic energies, and haptic communication coinciding. Further to this, a live experience could involve sensing sound vibrations, having collective emotional responses during a live occurrence, bodies moving or performing in a physical place, and a tangible atmosphere from people who constitute the space. This resonance passes from one person to the next, generation to generation, cannot be contained and can traverse physical space and computer screens. We can understand liveness in either the context of contemporary live art or public life, such as within music concerts, protest, dancehalls, club nights, marches, cookouts, and places of worship. A live experience’s dynamism is to do with how histories and presents; bodies and space; the planned and unplanned; coalesce and harmonise, contradict and conflict with another like Deloris’ choir in Sister Act. I describe my curatorial practice as aspiring to this coalescing and embodying liveness—relational, ever-evolving and frequential.

‘Curatorial frequency’ is a term I coined that allows me to articulate the physicality of curatorial practice when working with time-based media and discursive programming; this includes energy exchanges, transmission, movement and pace (both literally and metaphorically). Curatorial frequency is a meaning-making and a decoding process. It is a process of trial and error, channelling, and an embodied practice that actively contributes to how art or knowledge is experienced and disseminated in a moment of liveness. It is concerned with decoding nonverbal experiences and communication, establishing the quality of space in which the artist or audience can be receptive to meaningful messages. My approach to curatorial frequency involves having co-production to develop and sustain relationships with people and spaces, which can exist ephemerally, long-term or cyclic. The work I undertake, or aspire to undertake, is epistemological and is concerned with ways of being in dialogue with Diaspora and people from the Global South. I believe myself and the communities I am part of hold living histories within their bodies—trauma, joy, ancestral spirituality, rhythm, and cultural memory—developing and evolving languages within black performativity. I often try to explore more spiritualistic readings of work and employ movement to comprehend what it feels like to experience live art in a moment of restriction and inactivity. It is about language and contemplation through action or response, to stay present with yourself but curate programmes that sustain a presence. When I miss engaging with a live performance or time-based media, considering my curatorial practice and presence in this way has carried me through this challenging time. The process has allowed me to think of the enjoyment of being in someone’s presence and being public as an essential part of what I do. Sustaining human connection as a process of healing and coming to consciousness doesn’t seem so futile.

(1) There are many forms of curatorial practices beyond traditional exhibition-making, such as broadcasting time-based art (sound art, moving image etc.), creating and holding discursive, community and educational spaces. Curating does not have to involve working directly with artists. Curators work with other people who are not artists and engage in activities that explore themes concerning art and culture.

(2) Stuart Hall, Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse, University of Birmingham. Accessed 7 April 2021.

(3) See https://www.womenandperformance.org/ampersand/29-1/campt

(4) See here https://performingborders.live/residences/east-street-arts-residency-jade-montserrat/

(5) In reference to Saidiya Hartman, The Terrible Beauty of the Slum, 2017

(6) Read Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, 2019

(7) Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, 1968, Grove Press, New York, p. 35

(8) In reference to Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, 2016

(9) Definition—The time span of immediate consciousness: interval within which what is earlier may be distinguished from what is later though both are directly present to consciousness.

Jade Foster (b. 1996) is a British curator and artist (sometimes artist-curator) of Caribbean heritage. Foster holds positions as Assistant Curator at Primary and Creative Programme Coordinator at New Art Exchange (NAE) in Nottingham. As a freelancer they have worked with organisations and platforms such as Derby QUAD/FORMAT International Photography Festival; Derby Museums; Nottingham Contemporary; UK New Artists (formerly UKYA), and recently with the Live Art Development Agency (LADA), Centre for Contemporary Arts (CCA) in Glasgow as a Curator/Consultant, and Glasgow International.

As a neurodivergent writer, Jade's research interests include Utterance, Speech Act, Intersectionality, black feminist imagination, queer theory, decolonial studies, and curatorial practices coming from places of lived experience. They are currently writing an essay for LADA, reflecting on moments or shifts within Live Art between 2008–2020. The writing will be in conversation with an essay by David A. Bailey, MBE titled Performance-Based Art and the Racialised Body. David’s essay looks at the history of black British performance from the 1960s to 2008.

Jade is also a Board Member/Trustee of Nottingham Contemporary and the founder and initiator of Black Curators Collective (BCC).

Website: www.jadefoster.co.uk

Instagram: If you are PoC and queer (@jamaican.zaddy)

If you are not queer (@_jade_foster)

The Exhibition is in Transit vol.1 features contributions from Cédric Fauq, Cosmos Carl, Jaakko Pallasvuo, Jade Foster, Martí Manen, P*D*A*, Tal Gilad and Winnie Herbstein.

Ephemeral Care focuses on ethics, practice and strategies in artist-led and self-organised projects.