Cinema might seem like a small thing in a time like this. But there is power in film and in community. When we are abiding by the rules of physical distancing, staying at home to protect ourselves and others loneliness and mental health become major factors. Community networks are thus key, and community cinemas and film societies are showing just how important they are, not only now but always.

GIULIA BUSETTI: Community is a pivotal topic for Ephemeral Care, and I am curious to know more about the point of view of the cinemas on this. How did you start?

ALICE MAESTRINI: I came across Screen25 back in 2017, when it was still known as Stanley’s Film Club. I had just finished my master’s degree and was looking to get some experience in film exhibition. Katie, who founded the cinema, was looking for someone to help her in running and promoting the screenings.

You find yourself doing all sorts of jobs: from programming to marketing to doing budgets to projection to writing funding applications to cleaning toilets to host screenings.

Much, if not everything, has changed since then. We have adapted to what people needed and what the word hinted at us.

GB: You mean the community has agency in a community-led cinema?

AM: Well yes, you have the two-fold situation of South Norwood community and the cinema, more related to Screen25 community, but this is just a start. As we all know It’s always hard defining what a community is. Is it just people living within a certain place, sharing an identity or belonging to a certain place and lifestyle? We often give (and are given) labels that people don’t recognise themselves in. Self-determination is sporadic.

For me, the people who are coming to our screening and engage afterwards to talk about the film and their life and what they think about this and that, that’s a community. But do they recognise themselves as such? In working with communities as well as in regeneration projects - you need to ask yourself “is this benefitting me more than everyone?” If yes, take a step back.

GB: I am aware of the cliché, but It’s hard for me to think about community in such a big city like London. Maybe is just not something you hear about, rather something you experience.

AM: South Norwood hasn’t been gentrified as much as other areas in London (yet) but I was just reading the other day how it got one of the biggest increases in rental searches in all London.

People in the neighbourhood always come to us and ask if we need anything, if so they lend it to us, they make us feel welcome and make us perceive a sort of bond. There is mutual cooperation that still survives.

I personally think, but I’m sure I'm not alone, the word community itself has been tremendously instrumentalised. It’s a ubiquitous presence in funding applications or politicians speeches, especially now with the London mayoral elections coming up in a couple of weeks. I can think about three concrete examples of what I mean with community that goes beyond the community involved in the selection of the films to project. In one of the last "pay as you feel" events, that we organise each month with a different association, we showed a documentary about Bob Marley and cooperated with the South Norwood Community Kitchen, on the occasion of one of their Saturday lunches organised for homeless people and all who struggle in finding money for food. People came to the cinema straight after lunch, probably a totally unexpected surprise to them. They stayed there and told us they hadn't been to a cinema for years or told us about the last time they had seen a film. You could see it meant a lot for them.

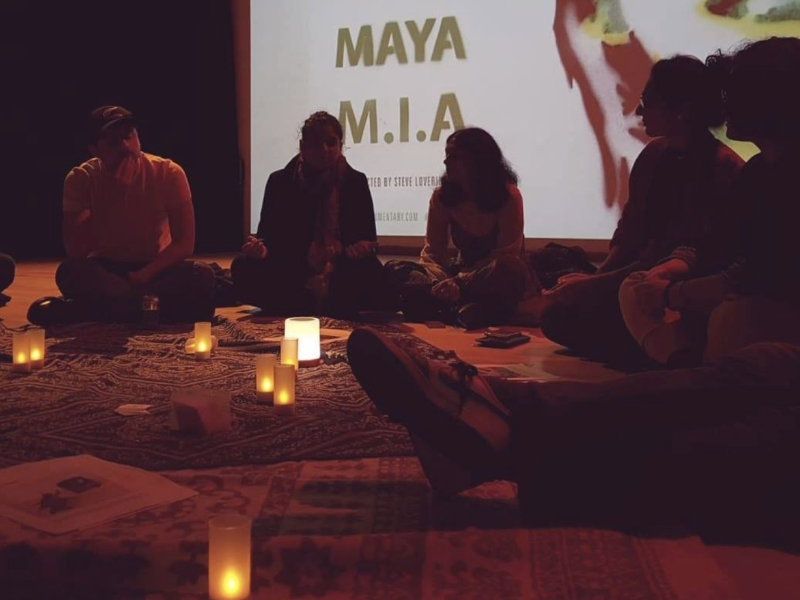

On another occasion we showed MATANGI/MAYA/M.I.A, also a documentary, that deals with the musician’s innermost reflections on art, politics and identity. Following the screening we hosted a panel discussion with Yalla Hub, exploring themes of migration, politicised identities and intersectional feminism, in context to experiences in the UK.

Many people joined that conversation sharing their personal stories, and concretely showing the “diversity" we are used to reading on grants requirements or programming goals. The third example that comes to my mind is the screening of Sorry We Missed you by Ken Loach, the story of a young man searching for freedom as a self-employed delivery driver, that took place the day after the election victory of Boris Johnson. As you can imagine the mood was not great that evening. You could feel the frustration in the room during the discussion on precarious work with representatives of the Trade Union Congress, London Living Wage, and of course, a majority of precarious workers, including us organising the event. We had very intense conversations that continued afterwards.

GB: It sounds like you have a very direct relationship with your audience.

AM: There’s a core group of people that have watched films with us since 2015. They have followed us from venue to venue, mistake to mistake. They appreciate our openness and in response, they’re honest with us. They give us feedback and say what they would like to watch the following week.

GB: So no problem at all during the pandemic.

AM: Haha! Right! Well on an (almost) positive note I can tell you that just last week we launched the “Screen25’s cinema on demand" campaign, 10 films people can watch from home for the symbolic price of £15. Many people donated the price of the subscription so we could cover the costs, but then personally told us they were not interested in watching films online (which is totally understandable after the whole day spent in front of the same computer screen). But still, they wanted to sustain the “Screen25 cause” waiting for the moment to gather again. This is a gesture that shows something in my opinion.

GB: Coming from the visual arts, I was thinking that there are some strong differences with the cinema in relation to the audience but probably more in general in the perception of the medium of film and its fruition; its position in the arts. Video art and Marvel films are sharing the same support but not the same struggles.

AM: For sure, film coexists as a cultural and “commercial” entity, a dichotomy that is more present in cinema than in visual arts for example. Everyone naturally experiences films in their life, through television, cinema, streaming. It’s not really a conscious choice, because we are used to doing it. Maybe with art, you need to be more proactive in a certain way. At the same time, “independent" films are more niche than independent (visual) art, it’s not usual to consider the social value of cinema, whereas cinema as entertainment is still the most accepted view.

Directly from here comes the funding issue. During the pandemic, we struggled (and still are) in finding funding. The British Film Institute (BFI), recognised for being engaged in a series of social requirements, provided funding for independent cinemas. However, only those with a certain amount of weekly screenings and a certain amount of rooms could access the fundings. Screen25 together with Peckhamplex and many other small cinemas were too small to meet the requirements, and the usual suspects got the funding. One example above all, as affordable arts venues fight to survive: the massive events company Secret Cinema got a huge bailout from the recovery found of the Arts Council England, and with huge I mean one million pounds (on this his topic I strongly recommend on Instagram: Department of Accountability @doauk 1). As I said, we wouldn’t have Screen25 without the support of our audience, and this is the most concrete way that is evidenced. In this case really "our community”.

GB: Yes that's quite impressive. There’s a very strong ground in the apparent ephemerality of community, probably due to different common senses, yet as an activating practice next to what Christoph Brunner 2 calls a militant, activist sense: “a common sense of emancipation that can sustain a different and radically democratic practice that is immersed in the dynamics and the contradictions of urban life.” This common sense responds to the possibility of being stuck with, as Nic Beuret 3 has beautifully paraphrased Donna Haraway 4, the vulnerabilities of social life. Are there also drawbacks about being community-led?

AM: It’s limiting relating to the films we can show, since we are not considered a “theatrical venue”. The distribution companies need a certain amount of weeks sometimes months before letting us show their films, which is a big hurdle. Also due to that in general there is not that much audience at our screenings.

To depend on a community and being independent means being precarious, we all have several job. Above all right now, we don't have a set location. Often community-led cinemas rely on other spaces, we have been hosting our screenings in an elementary school, until they increased the price 7 times. There is an external agency whose role should be “to facilitate the encounter between school and communities at an affordable price”, but their probably the only the only ones gaining something out of it.

To find a space is a real struggle for a cinema, more than it might be for an (visual) artist-run space. Not all the big halls can be used as a cinema. They need to meet specific requirements, also technically, you need to be able to install a projector, stock bar, and many other etceteras. And I’m not even talking about corona-restrictions, of course.

At the same time to go away from South Norwood would mean to betray that same community we are in a sort of pact with (without mentioning we would have to build a new community, whatever it means).

Even when we find potentially accessible spaces, it’s hard to legally establish a partnership since it is still unpredictable when we will be able to physically open again.

On the top of that, in November 2020 Croydon Council declare bankruptcy, a historical event that hadn’t happened since the 1970s. As you can imagine cultural life of the borough is not necessarily on the top of the to-do list of the Council, and this, for once, doesn’t have anything to do with the corona virus.

(1) https://www.instagram.com/d.o.a.u.k/

(2) Brunner, C. (2018) Activist Sense: Affective Media Practices during the G20 Summit in Hamburg in Technecologies, transversal 03.18 available at https://transversal.at/transversal/0318

(3) Beuret, N. (2018). The end of the world for whom?. new formations: a journal of culture/theory/politics, 93(93), 138-141.

(4) Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

INTERVIEW

Giulia Busetti & Alice Maestrini - APR 2021

The Reflecting on... series takes situations, objects, artworks, articles, texts, podcasts and anything else really as starting points for reflection on artist-led and self-organised (AL&SO) practice.

Ephemeral Care focuses on ethics, practice and strategies in artist-led and self-organised projects.