"The curatorial" is a term that I (miss)used frequently during my masters. Those two years of study were intended as a time to focus on my practice, try and figure out how curation and making worked together or against each other and which of these was the important part. It turned into two years of general trauma which I came out of not wanting to be a part of the art world anymore, but that’s not the point. One thing that kept coming up was “the curatorial” as a term. Whilst I wasn’t necessarily totally sure of the definition (or perhaps my definition), and that remains the case until reading Lind’s text, it felt like the right word to knit together the elements of the mess that was and is my practice.

Lind relates the notion of “the curatorial” to Chantal Mouffe’s notion of “the political”. Broadly speaking this pulls terms that are often conflated into opposition or at least adjacency. Politics/the political; curating/the curatorial.

“Mouffe argues for “the political” as an ever-present potential that cannot be precisely located, but which grows out of the antagonism between friend and enemy. “The political” is the aspect of life that is connected to disagreement and dissent, and is therefore an antithesis of consensus. For Mouffe, “politics”-as opposed to the political- is the formal side of practices that reproduce social and structural orders. With this in mind, the politics/political discussion can be mapped onto the curating/curatorial distinction, with curating -as opposed to the curatorial- as a technical modality we know from art institutions and independent projects. “The curatorial” on the other hand, would be a more distributed presence aimed at creating friction and pushing new ideas through signification processes and relationships between objects, people, places, ideas and so forth. “The curatorial” does not stop at the status quo.”1

Put briefly curating and politics are the act of doing something, the verb form. They are the nuts and bolts the “practicalities” so to say. They are functional. “The curatorial” and "the political” are about possibilities and opportunities and frictions and are adjectives describing a complex process that is nebulous and hard to grasp. As Lind goes on to state, curating is about redressing things to find a balance, to make things run smoothly, to get an exhibition from point A to point B with the audience strolling merrily alongside. “The curatorial” is more adversarial and slippery. It’s not necessarily interested in balance, it could be deliberately conflicting or antagonistic. It expects an audience to jog to keep up if needs be - cutting through a forest instead of strolling through a park.

The current political dynamic of the world at large has seen a general swing to authoritarianism and rightwing governments, as Lind also points out, has seen a rise in statements from “politically engaged art circles that art-making as we know it … cannot continue”2. Like Lind, I disagree and hold that now is the perfect time to be considering many of the points and references she highlights in her text. One of the most damaging elements of my time on the masters was during the first year when we were working with a local museum to install a set of artworks responding to and interacting with their collection. This process was in many ways derailed by one student and their choices. Those choices put us as a class, the school, the museum and the staff of both institutions in an incredibly difficult, toxic and unpleasant situation. Ultimately though it could have been avoided. An insistence on balance and, to a degree niceness, was what in many ways allowed the situation to spiral out of anyone's control. Whether it was a result of societal habits in Sweden (where I undertook my masters), political or pedagogical/ethical decisions by institutions or individual staff members, or simply a consequence of a group of people who didn’t know each other giving the benefit of the doubt I’m not sure.

Lind brings in the anthropological notion of “contact zones”, a concept developed by Mary Louise Pratt and James Clifford to describe “social spaces where various cultures collide and try to deal with each other”3 and “places of hybrid possibility and political negotiation, sites of exclusion and struggle.”4. These contact zones are conceptual spaces approached frequently in curating, the curatorial and arts education.

From a curating perspective, they may materialise in the points where the audience meets the artwork, how the artist or institution chooses to communicate or structure their space and allow folks to access the building and the contents within. In that nuts and bolts sense, we are talking about the texts associated with the exhibitions, the ways those exhibitions are played out, the languages used in terms of the system (English, Swedish, Kurdish, etc.), vocabulary and depth of content. Göteborg Konsthall has a good system where the latter is concerned featuring three levels of text: Paddlers, Swimmers and Divers.

Paddlers texts are shallow, giving a brief overview of the work/artist/concepts in a simplified manner. These are great for children, those with little time (or little interest) and those with poor reading skills or learning difficulties.

Swimmers texts are a little more complex and deep, providing readers with more information about the work/artist/concept whilst remaining accessible to the broadest possible audience. Some specialist knowledge may be helpful but isn’t expressly necessary.

Divers texts are more on the academic level, deep-diving into the concepts and perhaps bringing in other references, possibilities and links to previous or upcoming programming. These are for those who have a critical interest in the exhibition and specialist or at least broad knowledge of a range of fields. They can however exclude many audiences so aren’t necessarily what you want to lead with.

To use this analogy the contact zones of curating are probably paddler and swimmer level on the whole. Considering “the curatorial” however, we find ourselves in deep water pretty much straight away. There are greater demands present here both in terms of inference and deduction and general comprehension but also in terms of emotional intelligence to understand when there is deliberate antagonism and to understand that in the same way as anthropological “contact zones” these intellectual contact zones are “conflictual rather than consensual” by nature.

Going to an exhibition for the first time is like going on a first date. You maybe know the person to a degree from Tinder or a chance encounter in a bar (oh, those halcyon days) but ultimately there is a degree of trepidation, anxiety, tension. As with a first date, an exhibition has some kind of packaging that you find attractive which keeps you in the room but negotiating that contact zone Often in these situations, that first meeting can be slightly conflictual with each other's views and experiences grinding against one another to find an equilibrium of the things you agree on and experiences you have shared.

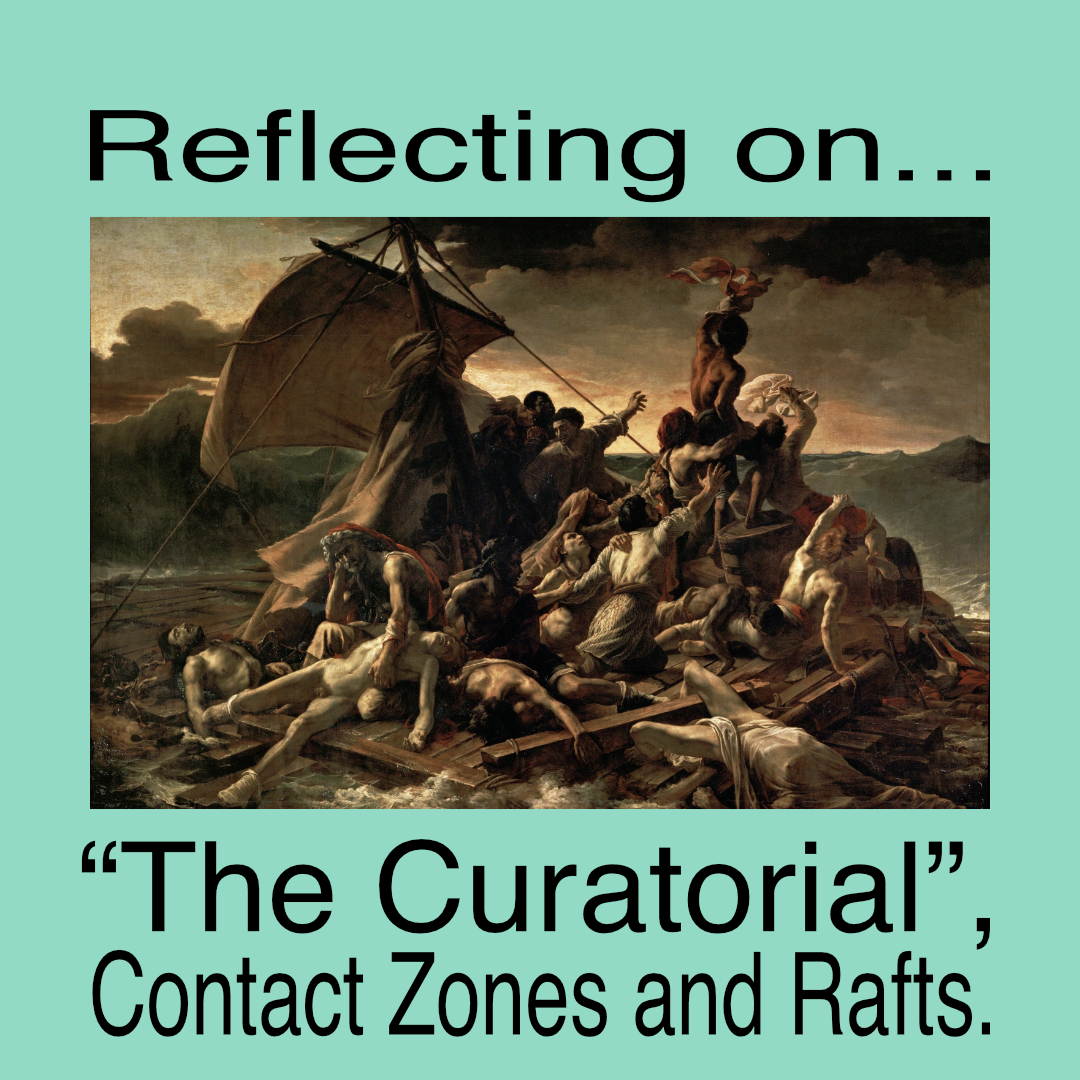

Pedagogical contact zones are more complicated however, I think. You are already committed to a long-term relationship with the people you're sharing that experience with. There are negotiations of character, new city, possibly new country, wanting to have friends, focus on yourself and your own work, pressure from teaching staff, external commitments or yourself. You are constantly forced to stay in the deep water with a variety of real or imagined concerns or pressures patrolling between you and the shore with poles ready to push you back into the blue if you try to pass. In these circumstances a certain blinkered aspect can take hold, concentrating on keeping your head above water and not necessarily spotting the dangers circling below. Evasion of conflict in these situations, as was perhaps a condition of our interactions in crits with this problematic peer, can feel like a means of self-defence. An attempt at maintaining a level of solidarity and mutual support, some kind of flimsy raft in the academic ocean.

“The curatorial” as this space of friction, conflict, tension and possibility necessitates a level of care and a level of acceptance that things aren't always going to be easy. Riding that raft in the middle of the ocean you have to anticipate, and perhaps more importantly respect and accept that the sea will become rough. There needs to be a degree of awareness at all times. Once you have that acceptance and awareness nailed and you have taken stock of the position you are in you can start to navigate to calmer waters.

Abandoning this now laboured metaphor, I will leave you with one final thing point raised by Maria Lind which I think hits on something vital and forgotten wayyyyyyyyy too often by academia, institution and I suspect many of us trying to make our way in the art world. Emotionality is something that exists and has to be allowed for. In my experience within both academia and in applying for jobs at art institutions I have hit upon the inference of emotion being the enemy, or at least something “unprofessional” we should seek to eradicate from our clean and pure neoliberal (but outwardly radically leftist) bodies. Lind touches on it in reference to George Katsiaficas’ 1989 essay “Eros Effect” and the author's assertion that the “emotional dimensions of social movements are just as important as their political dimensions.”5. In the same way as we drew a parallel between political and curatorial earlier, I believe we can now also. It is negligent to the mental health of ourselves and those we work with to suggest that emotion is not a player in the work of curators and artists and it's farcical to suggest that it isn’t something we play upon in audiences. If I wasn’t emotionally invested in a subject, why on earth would I care enough to make an exhibition about it? Or an artwork? Or write a song or a book? Or stand in the cold holding a sign and getting beaten up by the police? It feels self-evident that, as Katsiaficas, Lind, and Franz Fanon to boot, suggest -social movements have always been both emotional and rational political acts. Lind positions the struggle for liberation as “equally an erotic act and a rational desire to break free from structural and psychological barriers”6. Framing that through “the curatorial” and other definitions by academics advancing “the curatorial” as a field, considering it as knowledge production, knowledge collation, communication, networked or constellation thinking, whatever we see a framework of rationalism but we must never forget that at its core is that emotional need to frame something that we find important as culturally sophisticated animals.

Bringing it back to where I started with "the curatorial" as a term and a concept that feels right in terms of tying my practice into something more cohesive, I would like to highlight something from the last paragraph which I wish I had reflected on during my masters. There are many definitions of "the curatorial" and as long as you are happy in your definition of it, and can position yourself within that definition, fine. As with many concepts, there is a plurality of definition and we are allowed to choose the definition, or blend of definitions, we want to use to frame our work.

(1) Lind, Maria. e-flux. 2021. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/116/378689/situating-the-curatorial/ (accessed: 2021.02.04)

(2) ibid.

(3) ibid.

(4) ibid.

(5) ibid.

(6) ibid.

ESSAY

Joe Rowley - APR 2021

The Reflecting on... series takes situations, objects, artworks, articles, texts, podcasts and anything else really as starting points for reflection on artist-led and self-organised (AL&SO) practice.

Ephemeral Care focuses on ethics, practice and strategies in artist-led and self-organised projects.